GUATEMALA’S

Social revolution

In December of 1944

Jose Arevalo, a university professor became the first elected president of

Guatemala. Under Arevalo a new

constitution was written which included provisions for a strong presidency, an elected

representative body, and a supreme court.

Arevalo’s administration allowed unprecedented freedoms but was still

considered moderately conservative.

Teachers and some industrial workers were allowed to unionize somewhat,

but were denied the right to strike. The

new government made no provisions for the organization or representation of the

rural peasantry, which made up 70%-80% of the population. Also, under the new administration the army

remained very powerful and for the most part outside of the control of the

government.

As Arevalo’s term was

coming to an end, there appeared to be two possible successors. Major Francisco Arana, who was backed by

conservative interests, attempted to secure his ascension to power by seizing

the presidency from Arevalo in 1949.

Arana was killed by forces loyal to Arevelo. This solidified the succession of his chief

rival Jacabo Arbenz who was also a former military officer, but was far more

progressive than Arana. Arbenz won the

elections of 1950 by a landslide, but no one suspected that he would attempt to

implement widespread social change.

Arbenz primary goal was economically developing Guatemala so that it

could become independent of foreign influence.

He soon found that the only politicians that shared his view for

empowering the country were those of the far left, including the communists.

(Karabell 97-100)

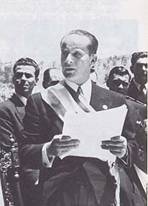

President Jacabo Arbenz

www.nodo50.org/cbc/ noticia/manual.htm

Arbenz’s plan for economic

development centered on reforming the feudalistic land divisions of the

Guatemalan countryside. In 1952 he

presented Decree 900 to the representative assembly. This was a land reform bill that he had drawn

up with the help of his close advisors, many of whom were communists or had

communist leanings. The decree was more

capitalist than communist, however, as it divided land into individual holdings

instead of collectivization. The land reform initiative took conservative and

moderate Guatemalans by surprise. It was

opposed by land owning Ladinos, the

Catholic Church, and the conservative press.

Arbenz went through with the plan despite the opposition. Under Decree 900 uncultivated lands on

estates over 675 acres were subject to expropriation. The former land owners would be compensated

with 25 year bonds based on the value of the land as was reported on property

tax returns.

Bananas-

a major cash crop

www.mdweil.com/ banana_tree_lg.htm

In order to bring about this land

reform Arbenz formed an agrarian based bureaucracy. This organized and politicized the

country-side, something entirely new.

This alarmed conservative land-owners as well as the middle class because

empowering 75% of the population that had formerly been politically dormant

threatened the power structure of the country.

For the most part Arbenz agrarian reform was a success. In 18 months 100,000 peasant families

benefited from the redistribution of lands.

During this same time agricultural production remained steady. Of Guatemala’s 341,000 landowners only 1700

were affected by the expropriations, but these 1700 had previously owned about

half of Guatemala’s arable land.

Arbenz’s plan for economic development also

included a replacement of foreign controlled infrastructure. His first focus, however, was land

reform. While he was focusing on the

countryside the urban populations began to feel neglected and uneasy about the

empowerment of the peasantry. This

public was easily influenced by the conservative land-owners and press and soon

questioned Arbenz’s loyalties and affiliation with the communists. (Gleijeses

453-475)